talks about why it’s not too late to save the planet.

“You want the truth? It’s hopeless. It’s completely hopeless.” That’s what Patagonia founder and chairman Yvon Chouinard told the L.A. Times about the plight of the earth amid climate change. In 1994.

Regardless, Chouinard and his company have spent decades—and millions of dollars—fighting for environmental causes around the world while investing in more sustainable business practices. What’s more, Patagonia has embraced and promoted the B Corporation movement, while Chouinard led such efforts as 1% for the Planet, a collective of companies that pledged to donate 1% of sales to environmental groups and has raised more than $225 million since 2002. Meanwhile, over the past 46 years, Patagonia has become a billion-dollar global brand, making it the ultimate do-good-and-do-well company.

But Chouinard remains unsatisfied. The 81-year-old is more focused than ever on demonstrating, by Patagonia’s example, the lengths a company can go to protect the planet. During a break from fishing near his Wyoming home, Chouinard is both passionate and wry in discussing his business philosophy, what we get wrong about sustainability, why he’s so excited about regenerative agriculture, and Patagonia’s rising political machine.

Fast Company: How do we cope with the idea that to be in business means we are polluters and hurting the planet?

Everything man does creates more harm than good. We have to accept that fact and not delude ourselves into thinking something is sustainable. Then you can try to achieve a situation where you’re causing the least amount of harm possible. That’s the spin we put on it. It’s a never-ending summit. You’re just climbing forever. You’ll never get to the top, but it’s the journey.

About eight months ago, you wrote a new mission statement for the company: “Patagonia is in business to save our home planet.” What impact has that had so far?

It’s affected every single person’s job. Some more than others, but it’s got everybody thinking. We’ve made a commitment to be fossil-fuel-free by 2025. We’re invested in companies that are working on growing synthetic fibers, stuff made from plants rather than petroleum. We’re not just cleaning up our act in our own buildings and stuff; we’re going around to our suppliers and convincing them to use cleaner energy. Then we’re continuing to work on saving large areas of the planet that capture a lot of carbon. I’m personally working on a new state park down at the tip of South America, about 800,000 acres of peat bogs and swamps and 200,000 acres of sea, that sequesters more carbon than almost anywhere in the world.

Ten years ago, you started getting into the food space, launching Patagonia Provisions and working on regenerative agriculture. Now you’ve been bringing those regenerative principles to your cotton supply chain. Did you always see that as the ultimate path?

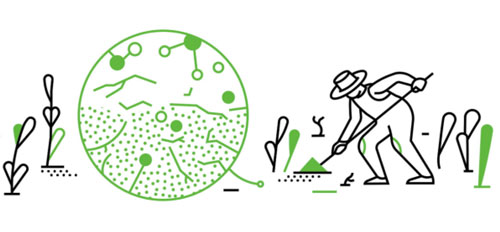

This is all pretty new. Scientists are just discovering how important agriculture is to climate change, both negatively and positively. [Environmentalist and entrepreneur] Paul Hawken has a book that lists 100 things that we can do to combat climate change [Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming]. Out of those 100, the most important that applied to us was agriculture, so we’re doubling down on regenerative organic agriculture. We’re working on a new certification that goes beyond organic. We’ve been using organically grown cotton for years, but all it does is cause a little bit less harm. So we decided to start growing it regeneratively and organically. We started with 150 farmers in India, small-scale farmers. We talked them into growing cotton with a minimum amount of tilling. Even with cotton now, we’re sequestering carbon. This is a big deal. Regenerative agriculture can’t be done on a large scale. It just can’t. These people are getting rid of their bugs by squashing them with their fingers. They’re stringing up lights to attract the insects at night and using natural methods. Then they’re using cover crops—chickpeas and turmeric, for which there is a big demand. And they’re using compost. We’re paying them an extra 10%, so [between that and the cover-crop revenue] they’ve almost doubled their income. Next year, we’ve got 580 small farmers who will grow cotton this way.

What do you think of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk pursuing interplanetary travel and Mars and moon colonies because they don’t seem to believe that we can save our home planet?

[Laughs] I think it’s pretty silly. And not just silly, but it’s really a shame. The monies that are going to space exploration should be used to save our own planet right now. We’re in a triage situation. Things are so grim. It’s World War III. I lived through World War II, and I remember what the country had to do to mobilize. You couldn’t buy sugar. You couldn’t buy meat. Being French Canadians, we were lucky in that we got horsemeat. [Laughs] That’s what has to happen with this global warming business. Here we’re just wasting this money going to Mars. I want to start doing some T-shirts that just have a rainbow trout on it, the T-shirt, and it says, there’s no rainbow trout on Mars, or screw Mars. We gotta do that.

Fast Company: How do we cope with the idea that to be in business means we are polluters and hurting the planet?

Everything man does creates more harm than good. We have to accept that fact and not delude ourselves into thinking something is sustainable. Then you can try to achieve a situation where you’re causing the least amount of harm possible. That’s the spin we put on it. It’s a never-ending summit. You’re just climbing forever. You’ll never get to the top, but it’s the journey.

About eight months ago, you wrote a new mission statement for the company: “Patagonia is in business to save our home planet.” What impact has that had so far?

It’s affected every single person’s job. Some more than others, but it’s got everybody thinking. We’ve made a commitment to be fossil-fuel-free by 2025. We’re invested in companies that are working on growing synthetic fibers, stuff made from plants rather than petroleum. We’re not just cleaning up our act in our own buildings and stuff; we’re going around to our suppliers and convincing them to use cleaner energy. Then we’re continuing to work on saving large areas of the planet that capture a lot of carbon. I’m personally working on a new state park down at the tip of South America, about 800,000 acres of peat bogs and swamps and 200,000 acres of sea, that sequesters more carbon than almost anywhere in the world.

Ten years ago, you started getting into the food space, launching Patagonia Provisions and working on regenerative agriculture. Now you’ve been bringing those regenerative principles to your cotton supply chain. Did you always see that as the ultimate path?

This is all pretty new. Scientists are just discovering how important agriculture is to climate change, both negatively and positively. [Environmentalist and entrepreneur] Paul Hawken has a book that lists 100 things that we can do to combat climate change [Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming]. Out of those 100, the most important that applied to us was agriculture, so we’re doubling down on regenerative organic agriculture. We’re working on a new certification that goes beyond organic. We’ve been using organically grown cotton for years, but all it does is cause a little bit less harm. So we decided to start growing it regeneratively and organically. We started with 150 farmers in India, small-scale farmers. We talked them into growing cotton with a minimum amount of tilling. Even with cotton now, we’re sequestering carbon. This is a big deal. Regenerative agriculture can’t be done on a large scale. It just can’t. These people are getting rid of their bugs by squashing them with their fingers. They’re stringing up lights to attract the insects at night and using natural methods. Then they’re using cover crops—chickpeas and turmeric, for which there is a big demand. And they’re using compost. We’re paying them an extra 10%, so [between that and the cover-crop revenue] they’ve almost doubled their income. Next year, we’ve got 580 small farmers who will grow cotton this way.

What do you think of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk pursuing interplanetary travel and Mars and moon colonies because they don’t seem to believe that we can save our home planet?

[Laughs] I think it’s pretty silly. And not just silly, but it’s really a shame. The monies that are going to space exploration should be used to save our own planet right now. We’re in a triage situation. Things are so grim. It’s World War III. I lived through World War II, and I remember what the country had to do to mobilize. You couldn’t buy sugar. You couldn’t buy meat. Being French Canadians, we were lucky in that we got horsemeat. [Laughs] That’s what has to happen with this global warming business. Here we’re just wasting this money going to Mars. I want to start doing some T-shirts that just have a rainbow trout on it, the T-shirt, and it says, there’s no rainbow trout on Mars, or screw Mars. We gotta do that.

climate change.

carbon rather than producing it. Here’s how it works.

During photosynthesis, plants use solar energy to extract carbohydrate molecules, or sugar, from carbon dioxide. Those carbon-based sugars are extruded from the plant’s roots, feeding bacteria and fungi into the nearby soil. Those microorganisms turn soil minerals into nutrients that feed plants and fight disease.

To keep the soil as healthy as possible, growers eschew chemicals (akin to organic farming), relying instead on natural methods—from hanging lights at night to physically removing and killing insects by hand.

In between seasons of growing cash crops such as cotton, farmers cultivate cover crops such as turmeric and chickpeas, which make the soil hardier by protecting it against nutrient loss and erosion, as well as helping to control pests. The farmers then have an additional crop to sell to supplement their income.

Tilling churns and disturbs roots—where most plants store a significant amount of their carbon—and other rich organic matter in the soil, making it less robust and productive. Even worse, it releases carbon into the atmosphere. By contrast, low- or no-till growing lets the carbon remain sequestered in the soil. Even when the roots decay, the CO2 emissions take a long time to reach the earth’s surface and atmosphere.

Log In

Log In  Language : English

Language : English